This section is intended for healthcare professionals

For general information about Mamma Mia just click the Mamma Mia logo.

1. Executive summary of Mamma Mia

2. Demo for healthcare professionals

3.The scientific background

4. Published RCT and studies

5. Monitoring with EPDS for symptoms of perinatal depression

6. The cost of perinatal depression in the UK

7. List of references for the scientific background

Content:

1. Executive summary of Mamma Mia

Mamma Mia is an evidence-based self-help intervention suitable for all perinatal women.

The tunneled programme follows the woman’s journey with 44 interactive sessions during a period from gestation week 21 until 6 months after birth. With 16 sessions prepartum and 28 sessions postpartum.

The women can sign up at any time during pregnancy and after birth.

There are separate tracks for women with female partners and women with no involved partner.

The pictures in the programme show ethnic diversity, and there is no advertising or other commercial content.

The programme does not collect last name, email address, or phone number. The women are anonymised with a 24-character, randomly created UserID.

The women complete the Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 7 times during the programme.

Based on the EPDS scores, the programme provides individualised follow-up.

The programme focuses on three important areas that influence mental and physical health throughout pregnancy and after birth:

The mother and child relationship

The partner relationship and social relationships

The woman’s mental well-being

Mamma Mia has been developed by Changetech, Oslo, Norway.

Changetech also holds the international commercial rights for the programme.

The effects of Mamma Mia have been thoroughly documented in one randomized controlled trial and other studies shared on this site. Two ongoing randomized trials, one in Norway and one in the U.S., are currently replicating and examining the effects of Mamma Mia using various support models.

Mamma Mia is documented to increase subjective well-being during pre- and postpartum and to reduce the risk for perinatal depression by 25% in the risk group.

The Regional Center for Children and Adolescents Mental Health (RBUP), Eastern and Southern Norway, has contributed with professional guidance to the content and has conducted research on the effects.

The Norwegian Women’s Health Association has contributed to the funding of the development of the programme and the research.

The Research Council of Norway has funded the RCTs.

The RCT conducted by the Virginia Commonwealth University was funded by the National Institutes of Health, USA.

2. Demo for healthcare professionals

In this demo for healthcare professionals, we focus on the background, structure and the documented outcomes of Mamma Mia.

You will also see examples from selected sessions and a full “live” session.

After the introduction you can choose more specific information.

To see the whole programme, please ask for the Open Version for healthcare professionals.

Please note that the demo only works on mobile phones, not PCs.

Scan with your mobile if you see this on your PC:

3. The scientific background for Mamma Mia

The theoretical foundation of Mamma Mia is based on Changetech’s evidence based platform for development of behavioural change interventions including:

Self-determination theory

Self-efficacy

Self-regulation theory

Positive psychology

Motivational interviewing

Cognitive behavioural theory

Metacognitive behavioural theory

Affect regulation and detached mindfulness.

For the development of Mamma Mia, the theoretical framework also included:

Risk and protective factors of perinatal depression

Perinatal depression and treatment

Therapeutic alliances

Couples therapy

The Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

The development process followed the intervention mapping (IM) protocol as descriptive tool, which consists of the following 6 steps:

1. Needs assessment

2. Definition of change objectives

3. Selection of theoretical methods and practical strategies

4. Development of program components

5. Planning, adoption and implementation

6. Planning evaluation.

The theoretical framework is further described in:

Drozd, F., Haga, S. M., Brendryen, H., & Slinning, K. (2015). An Internet-based intervention (Mamma Mia) for postpartum depression: Mapping the development from theory to practice. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(4), e120.

A white paper describing the psychological basis for Changetech’s platform for the development of behavioural change interventions can be found here.

For a complete Lists of references for the scientific platform please see the bottom of this page.

4. Published RCTs and studies of Mamma Mia

Since the release of the first web-based version in 2011, an RCT and other studies have been conducted to measure and understand the effects of Mamma Mia.

We have also collected a large quantity of in-programme data on usefulness, likes/dislikes, and free-text comments.

Based on this research and other feedback from the users, there have been many upgrades of the user interface and functionality from the early versions to the current phone app.

Here is a list of independent and published studies of Mamma Mia with short comments on the outcomes:

Published RCTs and studies by authors, study title and publication.

Haga SM, Drozd F, Lisøy C, Wentzel-Larsen T, Slinning K (2019). Mamma Mia – A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based intervention for perinatal depression. Psychological Medicine 49, 1850–1858. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002544

The RCT shows a reduction of symptoms and prevalence of perinatal depression of 21,5% to 26,6% in the risk group.

Haga, S. M., Kinser, P., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Lisøy, C., Garthus-Niegel, S., Slinning, K., & Drozd, F. (2021). Mamma Mia – A randomized controlled trial of an internet intervention to enhance subjective well-being in perinatal women. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(4), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1738535

The RCT shows a significant decrease in negative affect for women outside of the risk group.

Kinser, P. A., Moyer, S., Jones, H. A., Jallo, N., Popoola, A., Thacker, L., Russell, S., Olavesen, E. S., Sundrehagen, T., Hare, M. M., Xia, B., Garthus-Niegel, S., Haga, S. M., & Drozd, F. (2025). Perceptions of the Mamma Mia program, an internet-based prevention strategy for perinatal depression symptoms. PLOS Mental Health, 2(4), e0000138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000138

Participants found the program to be beneficial overall; they appreciated its guided content, focus on self-care, integration of mindfulness and educational components, trustworthiness, and activities such as breathing exercises and relaxation practices.

Drozd, F., Andersen, C. E., Haga, S. M., Slinning, K., & Bjørkli, C. A. (2017). User experiences and perceptions of internet interventions for depression. In S. U. Langrial (Ed.), Web-based behavioral therapies for mental disorders (pp. 27–52). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-3241-5.ch002

«Safe tutoring, with information tailored to my needs»

«It talks about the mental aspects in a good and natural way»

«I've become more aware and present»

«The exercises are comfortable, they help me find peace»

«You get information everywhere. This was easier to use»

«It's good to have something based on research and science»

«You get knowledge you can’t get anywhere else»

«I can use the meetings with health professionals much better»

«I really liked the techniques to get in touch with the baby»

«It's short, to the point and fun!»

Insights from the current review and study are used as a point of departure for discussing future directions in research on internet interventions for depression.

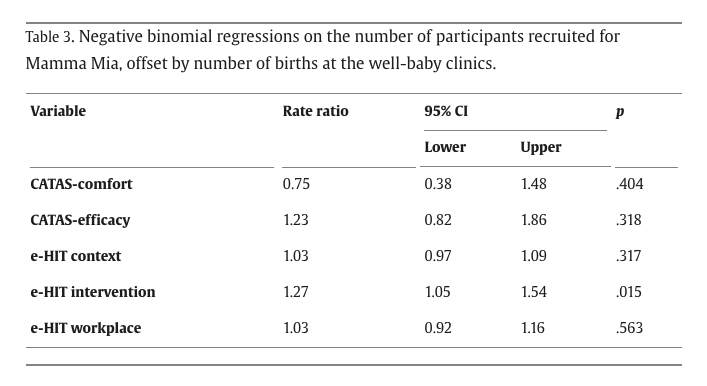

Drozd, F., Haga, S. M., Lisøy, C., & Slinning, K. (2018). Evaluation of the implementation of an internet intervention in well-baby clinics: A pilot study. Internet Interventions, 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.04.003

The rate ratio indicated that when a clinic's e-HIT intervention mean score increased by one point, there was a 27% increase in women recruited.

The evaluation shows that Mamma Mia is well suited to fit into the maternity pathway.

Drozd, F., Haga, S. M., Brendryen, H., & Slinning, K. (2015). An Internet-based intervention (Mamma Mia) for postpartum depression: Mapping the development from theory to practice. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(4), e120. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.4858

The IM of Mamma Mia has made clear the rationale for the intervention, and linked theories and empirical evidence to the contents and materials of the program.

Valla, L., Haga, S. M., Niegel, S. G., & Drozd, F. (2023). Dropout or drop-in experiences in an internet-delivered intervention to prevent depression and enhance subjective well-being during the perinatal period: Qualitative study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 6, e46982. https://doi.org/10.2196/46982

More than two-thirds of the women found Mamma Mia to be of high quality and would recommend Mamma Mia to others. Most also found the amount of information and frequency of the intervention schedule appropriate. Mamma Mia was perceived as a user-friendly and credible intervention.

5. Monitoring depressive symptoms using the EPDS

The Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is a questionnaire used to assess perinatal depressive symptoms during the past 7 days.

It was originally developed by Professor John Cox in Edinburgh, has gained wide acceptance, and is used in many countries.

In Mamma Mia, the women complete the EPDS 7 times during the full programme: In gestational week 23, 30, and 34, and in weeks 1, 5, 10, and 16 after birth.

Each woman is placed in one of three categories based on her EPDS scores.

Women with scores in the “low-risk” category do not receive additional support. Women with scores in the “medium-risk” category get additional in-programme support and a follow-up in the next session. Women with scores in the “high-risk” category get additional in-programme support and a recommendation to seek support from suggested healthcare services with a follow-up in the next session.

One of the purposes of Mamma Mia is to detect and prevent the further development of perinatal depression.

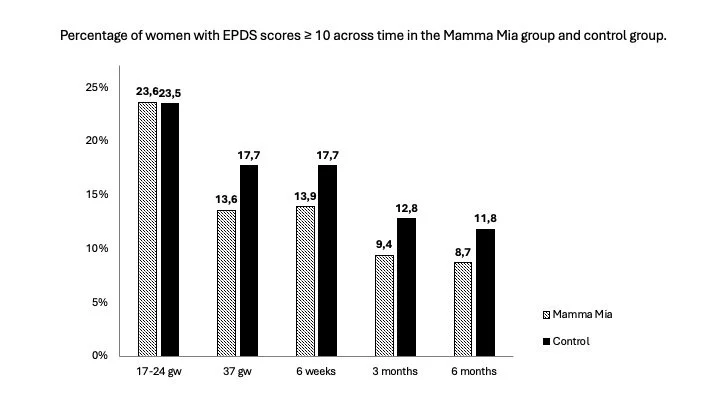

This graph shows the prevalence of women in group three (high risk for perinatal depression) at given intervals during the programme.

Both the RCT and the in-programme data show a reduction in the risk of perinatal depression at each timepoint.

In this graph this is shown as percentages of improvement from programme session 14 (gs week 35) and until programme session 30 (available from 5 weeks after birth).

The graph is based on data for 672 women over time.

NOTE. The data gathered in-programme indicates an increase in the prevalence of perinatal depression (in Norway) over the last years. (Data for sessions after S30 were not available at the time of publication.)

This graph shows the increase in high risk of perinatal depression (group three) in 2025 compared to data from the randomized controlled trial on Mamma Mia users published in 2018.

This increase further emphasizes the need for an effective low-threshold service like Mamma Mia to prevent perinatal depression among new and expectant mothers and relieve an already heavily burdened health system.

6. The costs of perinatal depression in the UK

Background.

An estimated 15–20% of new and expectant mothers experience depression, and this number is believed to be rising. (LSE 2014). Many do not receive the necessary help and support, leading to serious consequences for families, public healthcare, and society. Maternal depression can impact a child's development, contribute to pregnancy complications and mental health challenges, and even reduce the child's workforce participation later in life.

Groundbreaking research from the London School of Economics (LSE), commissioned by The Maternal Mental Health Alliance (MMHA), estimated that perinatal depression costs the UK £8.1 billion annually for each year's births.

The report from the London School of Economics (LSE). (2014)

This report, published in 2014 by LSE and the Centre for Mental Health, was officially launched in Parliament on 21 October 2014. It highlighted the urgent need for increased investment in perinatal mental health care, recommending that the NHS allocate £337 million annually to meet national care standards.

The findings are a core part of the Maternal Mental Health Alliance’s ‘Everyone’s Business’ campaign, which urges government and health commissioners to ensure that all women in the UK experiencing perinatal mental health challenges receive the necessary care and support, regardless of location or circumstances.

Since its release, there is reason to believe these figures have continued to rise.

The key findings of the report, led by Annette Bauer and Professor Martin Knapp from LSE's Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU), are as follows:

• The long-term societal cost of perinatal depression, anxiety, and psychosis is estimated at £8.1 billion for each annual birth cohort in the UK. • Nearly three-quarters (72%) of this cost stems from adverse effects on the child rather than the mother. • Over one-fifth (£1.7 billion) of the total cost is borne by the public sector, with the majority (£1.2 billion) impacting the NHS and social services. • Additional costs include loss of earnings, reduced work capacity, and diminished quality of life.

Despite clear guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and other national bodies on the treatment of perinatal mental illness, care provision remains inconsistent, with significant regional disparities:

• Around half of all cases of perinatal depression and anxiety go undetected, and many of those identified do not receive evidence-based treatment. • Specialist perinatal mental health services are crucial for women with complex or severe conditions, yet fewer than 15% of localities offer these at the recommended level, while more than 40% provide no service at all.

The follow-up report from the London School of Economics (LSE). (2022)

The follow-up report, “The economic case for increasing access to treatment for women with common mental health problems during the perinatal period”, outlined the economic and organisational pathway to increase the treatment of perinatal depression.

This report also includes a cost / benefit analyses and an analyses of workforce and budget required if governments were to decide to invest in the integrated service provision.

Click on the images to download the full reports.

8. List of references for the scientific background

Perinatal depression and treatment.

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen T, Pedersen C, Mors O, Mortensen P. New parents and mental disorders: A population-based register study. JAMA 2006 Dec 6;296(21):2582-2589. [doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582] [Medline: 17148723]

O’Hara M, Swain A. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8(1):37-54.

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1071-1083. [doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db][Medline: 16260528]

Musters C, McDonald E, Jones I. Management of postnatal depression. BMJ 2008;337:a736. [Medline: 18689433]

Banti S, Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Rambelli C, Ramacciotti D, et al. From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the perinatal depression-research & screening unit study. Compr Psychiatry 2011;52(4):343-351. [doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.08.003] [Medline: 21683171]

Lovejoy M, Graczyk P, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2000;20(5):561-592. [Medline: 10860167]

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011;14(1):1-27. [doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1] [Medline: 21052833]

Paulson J, Bazemore S. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2010 May 19;303(19):1961-1969. [doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.605] [Medline: 20483973]

Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Karyotaki E, Garber J, Andersson G. The effects of psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: A meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24(2):237-245. [doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0660-6] [Medline: 25522839]

Flynn HA, Blow FC, Marcus SM. Rates and predictors of depression treatment among pregnant women in hospital-affiliated obstetrics practices. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28(4):289-295. [doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.04.002] [Medline: 16814627]

Haga S, Drozd F, Brendryen H, Slinning K. Mamma Mia: A feasibility study of a web-based intervention to reduce the risk of postpartum depression and enhance subjective well-being. JMIR Res Protoc 2013;2(2):e29 [FREE Full text] [doi:10.2196/resprot.2659] [Medline: 23939459]

Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L. The pathway to care in post-natal depression: Women's attitudes to post-natal depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Pract 1996 Jul;46(408):427-428 [FREE Full text] [Medline: 8776916]

Buist A, Bilszta J, Barnett B, Milgrom J, Ericksen J, Condon J, et al. Recognition and management of perinatal depression in general practice—A survey of GPs and postnatal women. Aust Fam Physician 2005 Sep;34(9):787-790 [FREE Full text] [Medline: 16184215]

Dennis C, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth 2006 Dec;33(4):323-331. [doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x] [Medline: 17150072]

Prediction of perinatal depression

Haga SM, Ulleberg P, Slinning K, Kraft P, Steen TB, Staff A. A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: Multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. Arch Womens Ment Health 2012 Jun;15(3):175-184. [doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0274-2] [Medline: 22451329]

Haga SM, Lynne A, Slinning K, Kraft P. A qualitative study of depressive symptoms and well-being among first-time mothers. Scand J Caring Sci 2012 Sep;26(3):458-466. [doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00950.x] [Medline: 22122558]

Røsand GMB, Slinning K, Eberhard-Gran M, Røysamb E, Tambs K. The buffering effect of relationship satisfaction on emotional distress in couples. BMC Public Health 2012;12:66 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-66] [Medline: 22264243]

Røsand GMB, Slinning K, Eberhard-Gran M, Røysamb E, Tambs K. Partner relationship satisfaction and maternal emotional distress in early pregnancy. BMC Public Health 2011;11:161 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-161] [Medline: 21401914]

Proulx C, Helms H, Buehler C. Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam 2007;69(3):576-593.

Luhmann M, Hofmann W, Eid M, Lucas RE. Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 2012;102(3):592-615 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1037/a0025948] [Medline: 22059843]

Dyrdal GM, Røysamb E, Nes RB, Vittersø J. Can a happy relationship predict a happy life? A population-based study of maternal well-being during the life transition of pregnancy, infancy, and toddlerhood. J Happiness Stud 2011;12:947-962 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1007/s10902-010-9238-2] [Medline: 24955032]

Weinberg M, Tronick E. Emotional characteristics of infants associated with maternal depression and anxiety. Pediatrics 1998 Nov;102(5 Suppl E):1298-1304. [Medline: 9794973]

Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav Dev 2010;33(1):1-6 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005] [Medline: 19962196]

Barker ED, Jaffee SR, Uher R, Maughan B. The contribution of prenatal and postnatal maternal anxiety and depression to child maladjustment. Depress Anxiety 2011 Aug;28(8):696-702. [doi: 10.1002/da.20856] [Medline: 21769997]

Velders FP, Dieleman G, Henrichs J, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, et al. Prenatal and postnatal psychological symptoms of parents and family functioning: The impact on child emotional and behavioural problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;20(7):341-350 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0178-0] [Medline: 21523465]

Leis JA, Heron J, Stuart EA, Mendelson T. Associations between maternal mental health and child emotional and behavioral problems: Does prenatal mental health matter? J Abnorm Child Psychol 2014;42(1):161-171. [doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9766-4] [Medline: 23748337]

Korhonen M, Luoma I, Salmelin R, Tamminen T. A longitudinal study of maternal prenatal, postnatal and concurrent depressive symptoms and adolescent well-being. J Affect Disord 2012;136(3):680-692. [doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.007] [Medline: 22036793]

Pearson RM, Evans J, Kounali D, Lewis G, Heron J, Ramchandani PG, et al. Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: Risks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(12):1312-1319 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2163] [Medline: 24108418]

Crutzen R, Cyr D, de Vries NK. The role of user control in adherence to and knowledge gained from a website: Randomized comparison between a tunneled version and a freedom-of-choice version. J Med Internet Res 2012;14(2):e45 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1922] [Medline: 22532074]

Mayer R, Moreno R. Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educ Psychol 2003;38(1):43-52.

Drozd F. Treatment Effects and Consumer Perceptions of Web-Based Interventions [Doctoral Thesis]. Oslo, Norway: Department of Psychology, University of Oslo; 2013.

Lehto T, Oinas-Kukkonen H, Drozd F. Factors affecting perceived persuasiveness of a behavior change support system. 2012 Presented at: ICIS 2012: Thirty-Third International Conference on Information Systems; Dec 16-19, 2012; Orlando, FL p. 1-15 URL: http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2012/proceedings/HumanBehavior/18/ [WebCite Cache]

Brendryen H, Drozd F, Kraft P. A digital smoking cessation program delivered through internet and cell phone without nicotine replacement (happy ending): Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008;10(5):e51 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1005] [Medline: 19087949]

Brendryen H, Lund IO, Johansen AB, Riksheim M, Nesvåg S, Duckert F. Balance—A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of an online intensive self-help alcohol intervention. Addiction 2014;109(2):218-226. [doi: 10.1111/add.12383] [Medline: 24134709]

Atkinson L, Paglia A, Coolbear J, Niccols A, Parker K, Guger S. Attachment security: A meta-analysis of maternal mental health correlates. Clin Psychol Rev 2000 Nov;20(8):1019-1040. [Medline: 11098398]

Hayes LJ, Goodman SH, Carlson E. Maternal antenatal depression and infant disorganized attachment at 12 months. Attach Hum Dev 2013;15(2):133-153 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.743256] [Medline: 23216358]

Benoit D, Parker KCH, Zeanah CH. Mothers' representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants' attachment classifications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997 Mar;38(3):307-313. [Medline: 9232477]

Glaze R, Cox J. Validation of a computerised version of the 10-item (self-rating) Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Affect Disord 1991;22(1-2):73-77. [Medline: 1880310]

Spek V, Nyklícek I, Cuijpers P, Pop V. Internet administration of the Edinburgh Depression Scale. J Affect Disord 2008;106(3):301-305. [doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.003] [Medline: 17689667]

Larun L, Fønhus M, Håvelsrud K, Brurberg K, Reinar L. Depresjonsscreening av Gravide og Barselkvinner [Depression Screening of Pregnant and Postpartum Women]. Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2013.

Morrell CJ, Warner R, Slade P, Dixon S, Walters S, Paley G, et al. Psychological interventions for postnatal depression: Cluster randomised trial and economic evaluation. The PoNDER trial. Health Technol Assess 2009;13(30) [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.3310/hta13300] [Medline: 19555590]

Wells A. Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2009.

Bevan D, Wittkowski A, Wells A. A multiple-baseline study of the effects associated with metacognitive therapy in postpartum depression. J Midwifery Womens Health 2013;58(1):69-75. [doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00255.x] [Medline: 23374492]

Brugha TS, Morrell CJ, Slade P, Walters SJ. Universal prevention of depression in women postnatally: Cluster randomized trial evidence in primary care. Psychol Med 2011;41(4):739-748 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001467] [Medline: 20716383]

MacArthur C, Winter H, Bick D, Knowles H, Lilford R, Henderson C, et al. Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on womens' health 4 months after birth: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002 Feb 2;359(9304):378-385. [Medline: 11844507]

Drozd F, Mork L, Nielsen B, Raeder S, Bjørkli CA. Better days—A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based positive psychology intervention. J Posit Psychol 2014;9(5):377-388. [doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.910822]

Prediction of perinatal depression continued

Schueller SM, Parks AC. Disseminating self-help: Positive psychology exercises in an online trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14(3):e63 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1850] [Medline: 22732765]

Parks AC, Della Porta MD, Pierce RS, Zilca R, Lyubomirsky S. Pursuing happiness in everyday life: The characteristics and behaviors of online happiness seekers. Emotion 2012;12(6):1222-1234. [doi: 10.1037/a0028587] [Medline: 22642345]

Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15(5):593-600. [doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495] [Medline: 19432513]

Boehm J, Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon K. A longitudinal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness-enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cogn Emot 2011;25(7):1263-1272.

Sheldon K, Boehm J, Lyubomirsky S. Variety is the spice of happiness: The hedonic adaptation prevention (HAP) model. In: Boniwell I, David S, editors. Oxford Handbook of Happiness. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012:901-914.

Lyubomirsky S. The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want. New York: Penguin; 2007.

Pennebaker J, Chung C. Expressive writing: Connections to physical mental health. In: Friedman HS, editor. Oxford

Handbook of Health Psychology. Vol 7. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011:8712-8437.

Gottman J, Silver N. The Seven Principles of Making Marriage Work. New York: Three Rivers Press; 1999.

Gottman JM, Gottman JS. Gottman method couple therapy. In: Gurman AS, editor. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008:138-164.

Braithwaite SR, Fincham FD. A randomized clinical trial of a computer based preventive intervention: Replication and extension of ePREP. J Fam Psychol 2009;23(1):32-38. [doi: 10.1037/a0014061] [Medline: 19203157]

Rosenberg M. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. 2nd ed. Encinitas, CA: PuddleDancer Press; 2003.

Nugent J, Keefer C, Minear S, Johnson L, Blanchard Y. Understanding Newborn Behaviorearly Relationships: The Newborn Behavioral Observations (NBO) System Handbook. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing & Co; 2007.

Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin R. The Circle of Security Intervention: Enhancing Attachment in Early Parent-Child Relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 2014.

Cohen N, Muir E, Lojkasek M. The first couple: Using watch, wait, wonder to change troubled infant-mother relationships. In: Johnson SM, Whiffen VE, editors. Attachment Processes in Couple and Family Therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

Therapeutic alliance

Richardson R, Richards DA, Barkham M. Self-help books for people with depression: The role of the therapeutic relationship. Behav Cogn Psychother 2010;38(1):67-81. [doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990452] [Medline: 19995466]

Barazzone N, Cavanagh K, Richards DA. Computerized cognitive behavioural therapy and the therapeutic alliance: A qualitative enquiry. Br J Clin Psychol 2012;51(4):396-417. [doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2012.02035.x] [Medline: 23078210]

Bickmore T, Gruber A, Picard R. Establishing the computer-patient working alliance in automated health behavior change interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2005;59(1):21-30. [doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.008] [Medline: 16198215]

Bickmore T, Schulman D, Yin L. Maintaining engagement in long-term interventions with relational agents. Appl Artif Intell 2010 Jul 1;24(6):648-666 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1080/08839514.2010.492259] [Medline: 21318052]

Consolvo S, Klasnja P, McDonald D, Avrahami D, Froehlich J, LeGrand L, et al. Flowers or a robot army?: Encouraging awareness and activity with personal, mobile displays. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing. New York: ACM Press; 2008 Presented at: UbiComp '08; Sept. 21-24, 2008; Seoul, South Korea p. 54-63. [doi: 10.1145/1409635.1409644]

Kennedy C, Powell J, Payne T, Ainsworth J, Boyd A, Buchan I. Active assistance technology for health-related behavior change: An interdisciplinary review. J Med Internet Res 2012;14(3):e80 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1893] [Medline: 22698679]

Birss S. Transition to parenthood: Promoting the parent-infant relationship. In: Nugent JK, Keefer CH, Minear S, Johnson LC, Blanchard Y, editors. Understanding Newborn Behavior and Early Relationships: The Newborn Behavioral Observations (NBO) System Handbook. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 2007:27-49.

Gottman JM, Gottman JS. 10 Lessons to Transform Your Marriage. New York: Three Rivers Press; 2006.